History on the Rhyme

1954: "That entertainment disruption was the worst!" 1968: "Hold my beer."

Another “short post” that overran its boundaries. Please view it in its entirety in Substack, as it is likely too large for your e-mailer to handle.

Earlier this week, I read this article from

regarding Saturday Morning Cartoons and Action for Children’s Television (ACT) in the Great Year of 1968. You can now read about it on his Substack at the link below.Knowing a bit about comics, cartoons, and the Cultural Fracture Point of 1968, which preceded 1997’s Cultural Ground Zero, I dropped a link in a comment regarding why ACT and other organizations pushed to change the genre of cartoons on network television. I’ll drop that same link here for you a bit later in this article.

But, reading Brian’s article again, something clicked for me as to the events described in the article. Something familiar.

First, some background on 1968.

The Federal Government of 1968 was not the FedGov of 1954 as discussed in my previous articles on the Comics Code. The Eisenhower administration, especially in its second term had seen the Federal Government establish the Interstate Highway system, intervene in the Little Rock, Arkansas desegregation crisis, agree to the partition of Vietnam into North and South, and engage in many Cold War stand-offs with both the Soviet Union and China.

While Eisenhower’s focus was predominantly international, Kennedy’s New Frontier initiative was an example of renewed Progressivism on the domestic front. After Kennedy’s assassination — which was a significant blow to much of the American public, President Johnson continued in the vein of expansion of social programs and the attempted elimination of poverty with his Great Society program, ultimately spending upwards of $3 trillion in the failed effort.

In general, the Federal Government became much more willing to get involved in cultural, social, and economic issues between 1952 and 1968.

Social unrest was accompanying the Boomers’ entry into adulthood, along with the growth of the drug culture, and the escalation of the Vietnam War throughout the LBJ administration. Draft protests, draft card burning, and student riots and campus take-overs (often “sit-ins” to shut down administration activities and classes) were common in the mid- to late-60s.

These violent protests finally ended with the shootings at Kent State in Ohio on May 4, 1970 when National Guard troops fired on students and killed four. International relations throughout this period were marked by tensions between the US and the Soviet Union.

Stressful times.

But what was so special about 1968? Many historians identify that year as a cultural break point between the Greatest Generation and the Silents having the lead hand in driving cultural and social issues and the advent of the Boomers taking the lead in shaping culture. They weren’t alone in this though.

While the Greats and Silents were sending men into space, the wilder half of the Boomers were flooding the zone with their preferred cultural norms as “hippies”, “yippies”, and a few “zippies”. Some Boomers were off fighting the Vietnam War. Others with college deferments that allowed many of them to avoid the draft were studying for their Bachelor’s degrees and getting ready to graduate into the world of work in 1968.

Some thoughts on 1968, the year:

Now that we have set the stage, what was the big deal about Saturday Morning Cartoons in the 1960s?

Several studios were doing animation for the small screen in the late 1950s and the 1960s. These included:

Paramount Cartoon Studios (formerly Fleischer Studios)

Hanna-Barbera Productions

DePatie-Freleng Enterprises

Filmation

United Productions of America

Warner Bros. Cartoons, and

MGM Cartoons

The big dogs on the block for Saturday cartoon shows were William Hanna and Joseph Barbera from Hanna-Barbera Studios. The pair struck out on their own business after being released from the MGM movie studio where they worked making Tom & Jerry cartoon shorts.

The MGM shorts were made using full-animation techniques, producing highly fluid motions in the characters. The issue with this technique is that it takes a long time to produce even a short 10-minute cartoon. After leaving MGM in 1957, they began making their own animated characters using limited-animation techniques, as well as Xerography processes for copying, which was significantly faster than full animation.

The Ruff and Reddy Show was Hanna and Barbera's first TV venture. It premiered on NBC on December 14, 1957. The Huckleberry Hound Show followed close on Ruff and Reddy’s heels in 1958, winning an Emmy -- the first cartoon show to ever do so. After incorporating into Hanna-Barbera Productions, Inc., the pair followed up with The Quick Draw McGraw Show and Loopy De Loop. All this led up to the biggest Prime Time (evening) cartoon of the 1960s:

Yeah, before The Simpsons did it, Fred and Wilma were there for seven seasons. Note that both Top Cat and Jonny Quest were also Prime Time offerings from Hanna-Barbera when first broadcast. Check out this listing of Hanna-Barbera productions spanning several decades.

Click this link if you’d like to enjoy some Flintstones theme music.

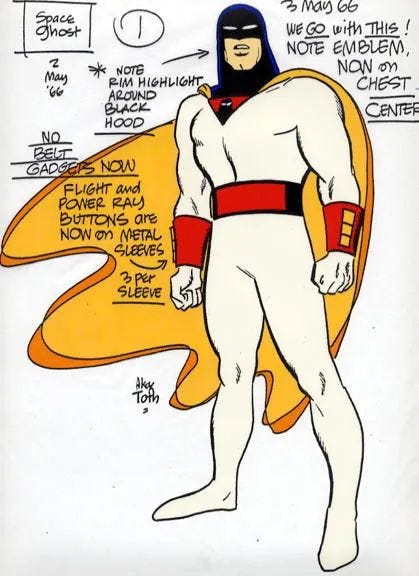

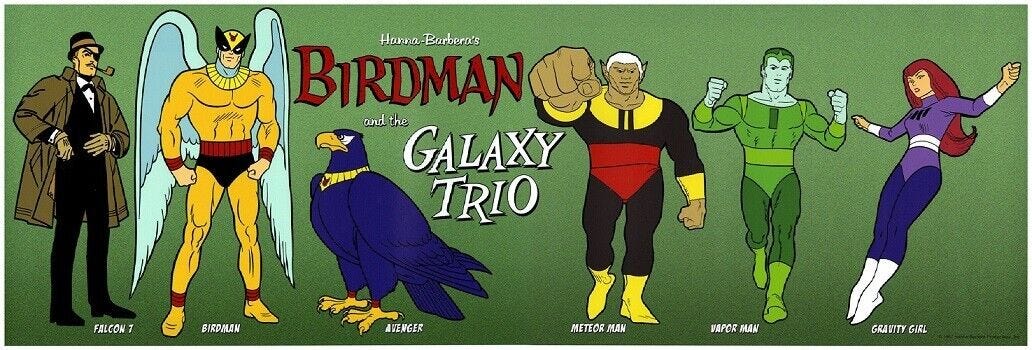

Hanna-Barbera had some of the best cartoon themes and incidental music around, thanks to the musical stylings of Hoyt Curtin. These jazz-infused themes tended to set the HB crew’s offerings apart from other studios. Take a listen to some of the themes from Jonny Quest, Space Ghost, and Birdman. Curtin also composed the theme for the American release of the Japanese cartoon Science Ninja Team Gatchaman, called Battle of the Planets in the States. Here’s a short video on Hoyt Curtin and his work.

Along with great music, the voice cast was top notch, featuring some recognizable personalities from the late 40s and 50s radio, TV, and movies, to include Paul Frees, Gerald Mohr, Daws Butler, Don Messick, and Mel Blanc. Newer voice talent included Gary Owens, William Marshall, and Tim Matheson.

Tim Matheson was the voice of Jonny Quest, Young Samson, Sinbad Junior, and Space Ghost’s Jace, as well as other characters in Hanna-Barbera animated features.

Gary Owens is familiar to some as the off-beat announcer of Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In. Owens provided the stentorian voice of Space Ghost.

And the booming, all-encompassing voice of Birdman was provided by opera-trained actor William Marshall, who some might remember in the role of Dr Richard Daystrom from Star Trek (the original series), or from the title role of the first Blacksplotation film, Blackula, or perhaps as the King of Cartoons from Pee Wee’s Playhouse, or the Captain of the Video Pirates from Kentucky Fried Movie. Marshall could give James Earl Jones’ voice a run for its money.

Here’s a video snapshot of what was on the schedule in the 1967 to 1968 season. Check out the video here.

To the video author: Sorry, dude, but Rocky and Bullwinkle creator Jay Ward’s George of the Jungle rocked.

That line-up should get any 7 to 12 year old boy interested in watching! And no small number of girls as well!

So what was all the fuss about with Saturday Morning Cartoons?

Well, as the link I promised you earlier states, there was concern that this new lineup of cartoons begun in 1966 was too violent for children. And, it was feared that children would learn to be violent from watching these shows.

What I noted was similarities between this event and the 1954 Comics Code wrangles, which I have written about previously. Link here for new readers.

Similarities / Correlations:

Action for Children’s Television ←→ Fredric Wertham & Parents

Commercial Broadcast Networks ←→ Bill Gaines’ EC Comics

Comic book artists ←→ Animation studios

US Government regulation and oversight potential in both cases

ACT was a non-profit organization engaged in “professional advocacy” funded by membership contributions and various foundation grants, rather than an unpaid coalition of parents, religious leaders, and civic organizations, as seen in the 40s and 50s. ACT’s initial focus was stopping the commercialization of children’s TV shows — attempting to remove promoted products or products based on characters in shows. ACT advocated to similar groups of parents who led community efforts against violent Horror and Crime comics in the 1950s.

Violence was the ACT target for Action-Adventure Cartoons of the mid- to late-60s. While advocating with the National Association of Broadcasters to impose limits on what could appear on children’s television, they also engaged in research efforts with the consumer advocacy group, The Center for Science in the Public Interest.

These activities by ACT marked a shift from community-based advocacy to a professional advocacy to the FedGov for policy changes regarding children’s entertainment.

Comic book artists and animation studios are pretty much 1-to-1 correlation on where they stand. They were asked to produce artwork according to a standard given by the comic book publishers and TV networks, respectively.

Bill Gaines and publishers in his vein behaved much like the TV networks asking for these action-oriented, cartoon-violence-laden, prime time shows: both were pushing the envelope as hard as they could, as long as the money was coming hard and fast. Again, we have the culprits who started the fires here with their lust for more fame and money. Kids are consumers to these guys. And the TV Networks? Dual-headed snake, as we’ll see.

The other wild card this time around was FedGov. More than willing to intercede on behalf of children in the 1960s, especially after RFK’s assassination. Ready to create a program to investigate the effects of violence on children, LBJ established the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence to investigate how children might be affected. Urged on by ACT and similar groups, parents, church, and civic groups began to pressure TV Networks to remove violent programming for children. Seeing the writing on the wall, networks ran out the last of the action-driven cartoons they had in the can in the 1969-1970 Saturday Morning Cartoon season.

This is where cartoons shifted back to the early 1960s in flavor, and where Scooby Doo and his comedic compatriots come in to the picture to dominate the 1970s.

So, as Brian pointed out, a bit of entertainment was whittled away for the 7-12 year old set, and was replaced with — nothing. Rather, entertainment types that were geared for a younger cohort (perhaps 5 to 8 years old) replaced some of the material enjoyed by their older siblings.

So, who lost out? If we look at the Generations List, we see that the likely impacted generation for loss of Action-Adventure Cartoons was Gen-X.

Shocker.

The Greatest Generation: 1914-1934

The Silent Generation: 1935-1945

The Baby Boomers: 1946-1956

Generation Jones: 1957-1967

Generation X: 1968-1978

Generation Y: 1979-1989

The Millennials: 1990-2000

Generation Z: 2001-2011

This pause in Action-Adventure Cartoons would last a decade, until roughly 1979-1980 when they once again began to emerge. Some of these, like the Japanese-made Space Battleship Yamato anime, named Star Blazers in the US markets, became highly popular as the no-violence iceberg began to thaw.

With Star Blazers, Gen-X was back in the fray to experience the return of the Action-Adventure Cartoon.

What about the two-headed nature of the TV networks? While the Entertainment side of the networks relegated violence to the dustbin for a decade, the News side glorified violence in their broadcasts, showing footage of war, riots, revolutions, and other violent acts.

News shifted from more neutral reporting of events in the 1950s to an ever-more activist and opinionated newsroom, willing to give a listening ear to protests and social causes. In some cases, even give the events a healthy nudge if necessary.1

Thus, it’s possible that no net reduction in actual violence presented to children viewing network television after 1968 occurred due to the actions of the Entertainment and News divisions of any of the Networks, regardless of ACT’s apparent success in sweeping Action-Adventure Cartoons from the map in 1968. Imagine that.

The advantage we have today is that some of these 1966-1970 Action-Adventure Cartoons are available as reruns here and there, and some are even available as collections on DVD or Blu-Ray.

As a Jonny Quest and Space Ghost fan from way back, I strongly recommend you track these down and enjoy, and maybe you will judge them appropriate for your kids as well.

This was exemplified by Walter Cronkite's "We Are Mired in Stalemate" Broadcast on February 27, 1968. Cronkite had returned from covering the Tet Offensive, and claimed that the War had ground to a halt. In fact, the Tet Offensive was a decisive victory for the US and South Vietnamese forces.

The White House was shocked by the reporting, and President Johnson reportedly said, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.” Also untrue based on polling data, but it turned the tide of the war for the President.

The Mainstream Media had achieved a political shift via lying. It would not be the last time such events occurred. Ah, enough of that.

Wokeness is a symptom of Herculoids Deficiency.

We rented Johnny Quest back in the day. I still have memories of my brother menacing random siblings with a butter knife, saying in a Mexican accent, "But Johnny, I am a nice guy! Unless you do not tell me where you find the Spanish doubloons!"

I need to find those for my kids. :-D