POSTS IN THE SERIES: Post 1 Post 2 Post 3 Post 4 Post 5 Post 6

Note 1: I am currently working on one or more posts discussing the American comics codes and their effects on publishing, as well as the furor(s) that surrounded them. Life has once again intruded these last few weeks, but with luck, sometime next week you should see the first one posted. In the meantime, I am reposting a series of six articles that I wrote about two and one-half years ago on American comic book history. I might make a few corrections along the way. We’ll see.

Note 2: I do not strive to be either academically rigorous nor authoritative in my analysis, and I’m an opinionated cuss. Other authors have spent a great deal of time interviewing the principle actors and performing rigorous historical research, therefore I lean heavily on those individuals who did the heavy lifting on this topic. My posts are meant to review some results of these researchers’ data and findings, as well as examining other artifacts of comic book history, to attempt to find general or overarching patterns that may inform and guide current and future creators of comics. References to the sources I use will be provided at the bottom of this and future blog posts.

Note 3: Some of these posts are gonna blow up your e-mail. Sorry ‘bout that.

HOW DO WE GET COMIC BOOKS INTO OUR HANDS?

These are a few brief opening thoughts on comic book distribution. I will return to the topic in a later post.

Much like Pulp Magazines, comic books started out their existence as print matter distributed by the same or similar organizations that distributed other magazines and periodicals. From 1937 to 1978, the Newsstand Model was the only way other than mail-order subscription that comics could be obtained, which was no different than the Pulp Magazine distribution model of the previous era. Comics were generally not well regarded by distributors due to their low profit margin (comics were priced at 10 cents per issue from 1937 to about 1960) and high return rate.

“Return rate”? What ever do you mean by “return rate”?

Return rate was the fraction of the total print run that was returned to the distributor by the retailers. Newsstand distribution in the years before the 1990s was based on a model of ‘pay for what you eat’. As an example, consider a retailer who orders 20 copies of Whiz Comics #25 from the distributor and places them on display until the pull date when they are supposed to go off sale and be removed from the rack. Over the course of 30 on-sale days, the retailer sells 17 copies of the comic book, then pulls the remaining three from the stand, likely to replace it with some number of Whiz Comics #26. The three remainder copies would be sent back to the distributor for a full or partial credit that could be applied to a future order. The return rate in this case would be 15%. See this Comichron page for an example of a Postal Service ‘Statement of Ownership’ and the yearly return rates versus actual sales.

Over time, rather than shipping back the entire book, the retailers were allowed to deface the cover and return proof of this action to the distributor. This usually entailed tearing off the top third or so of the front cover with the title and masthead, then returning these portions. While the retailers were supposed to dispose of the periodical after the book was defaced, it was not uncommon that these defaced copies would be quietly sold for half price or given away to customers. High return rates meant lower profits for both distributor and publishers.

Both newsstand distributors and comic book publishers were anxious to find another method of distributing comics during the Superhero heydays of the 1960s and early 1970s.

A brief aside: who were these retailers? Local comic shops? In the period between 1937 and the 1960s, exclusive comic book dealers were rarely found, and if found, they would likely not be outside a major metropolitan area. Newsstands were more common, but even they were not common outside heavily urbanized areas. The retailers of concern were located in urban, suburban, and rural areas: drug stores/soda shops, grocery stores, Five & Dime stores (such as Ben Franklin), gift shops, book stores, restaurants, convenience stores, and toy stores. Most any shop willing to devote about four square feet to a spinner rack and sign up with a newsstand/periodical distributor could have comic books.

These spinners or magazine racks were almost as common as paperback spinners, and served the same purpose: to catch the attention of customers browsing the store, or to occupy the attention of those accompanying the shopper. Often these tag-alongs to the shopper would be children. Many introductions to the comic book as an entertainment art form were made waiting for mom to finish the grocery shopping or while picking up that prescription at the drug store.

Direct-sale market proposals for comic books were considered, and a method acceptable to retailers was chosen in 1977/78, leading to a dual distribution transition period. Comics books were marketed to retailers by both newsstands and direct-market distributors for a period until about 1987 when the transition was essentially completed. After this point, direct-market distribution was almost exclusively to local comic stores that had grown up while the transition occurred.

Over the next decades, subscription services for comics would also vanish, leaving the local comic store as essentially the only game in town for comic book sales. Two significant changes resulted from direct-sales distribution: no returns — “eat all you take”, and potential minimum order numbers of selected issues — “take all WE want you to eat”. While good for distributors and publishers, these conditions would become a point of contention over time for both comic stores and their customers. These changes also made tracking the actual sales numbers of titles much more difficult, as distributors often didn’t release those data to the public.

The question I will leave at the end of this brief introduction to distribution of comic books is: who services the comic book readers in rural and small suburban areas that aren’t large enough to support a comic book store? Do hard copy readers even exist in these locales in the 21st Century?

Local comic shops — in my admittedly limited experience with only several dozen — don’t often appear in areas with populations under about 30,000 people. Few retailers of the newsstand method mentioned above chose to keep comics in their establishments with the overhead of using a second distributor for low-volume, no-return, low-margin profit items such as comic books. Comic books vanished from the pre-1978 retailer locations over an 8- to 10-year period. Much like the Thor Power decision, this impacted used book stores that traded in comics, as well as beginning to remove the comic book hordes from rummage and yard sales, swap meets, and other locations where used comics might be found. The old comic book owner was suddenly in the middle of a collectors market.

Enough of that discussion for now. It will serve as an opener for a more detailed distribution discussion later.

WHAT CONTRIBUTED TO MAKING 1960s MARVEL COMICS A SUCCESS, AND WHAT KILLED IT: THE 1968 SALE.

NOTE: I lean heavily on two sources for much of this section. The first is Chris Tolworthy’s site, “The Great American Novel”, which is a work-in-progress love letter to “The World’s Greatest Comic Magazine”. While I don’t agree with some of Chris’ analyses on what Kirby’s artwork intends, disagree with his interpretations of the FF saga character-by-character, and believe that the “Stan vs Jack” debate is a false dichotomy, his site provides a wealth of information on the Silver and Bronze Ages of Marvel Comics, as well as some pertinent DC Comics data. The other site of interest is Comichron. It gathers comic book distribution and sales data from the 1960s USPS Statements of Ownership, as well as Direct Market data from distributors — yes, plural–there was once many more of them than just Diamond — to provide rough snapshots of comic sales and popularity year-on-year.

The transition for comic book companies out of the Golden Age of Comics was not an easy one for most of the companies that survived the downturn in superhero comics popularity after World War II, the congressional hearings on suitability of comics for children (see, Fredric Wertham), and their own poor planning for the audiences of the 1950s. Timely/Atlas was the precursor of Marvel Comics and was owned by Martin Goodman. Their superhero titles were pretty much shuttered by 1949 due to falling sales. These cancelled titles include Namor the Sub-Mariner, the Human Torch, and Captain America. Stan Lee was the company’s Editor — essentially the Editor-in-Chief, taking over from Joe Simon in 1941 until 1972 when he left that position to take the role of Executive Vice President and Publisher, roles he would hold until 1996.

But, Stan was more than an editor at Timely/Atlas. He was one of the primary writers for their stable of comics, which included horror, western, romance, mystery, and crime/detective books. Due to the loss of his distributor in 1957, Goodman was forced to cut and drop most of his current titles (see this article for how many books stop at 1957) and sign a contract with National Periodical Publications to distribute Atlas/Marvel comics. If you recall, National was the publisher of Superman, Batman, and other comics that are today known as the DC Comics stable.

Yes, that’s right. DC Comics (National Periodical Publications until 1977) distributed the 1960s Marvel Comics titles that eventually overshadowed their own titles. What a world! What a world! What a world!

The agreement did come with restrictions that Goodman could only publish a limited number of titles, which is thought to be one of the reasons that Tales of Suspense hosted both Iron Man and Captain America, Tales to Astonish variously paired Ant-Man/Giant-Man & the Wasp, Sub-Mariner, and the Hulk, and Strange Tales had split features of the Human Torch, Doctor Strange, and Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. It would also explain why the original book for the Hulk was cancelled after its sixth issue. If it wasn’t selling up to par, they needed that space for another title that did!

Stan started under the new distribution contract with the at least these titles in his stable:

Patsy Walker

Patsy and Hedy

Millie the Model Comics

My Own Romance

Love Romances/Teen-Age Romance

Journey into Mystery

Strange Tales

The Outlaw Kid

Two-Gun Kid

Rawhide Kid

Kid Colt, Outlaw

There may have been more titles that made it into the Marvel Superhero Era beginning in 1961 (I’m still researching that detail), but these 10 were there for certain. However, the biggest bonus Stan had at the time was the group of artists that gravitated to Marvel to work on these books. Jack Kirby, Joe Sinnott, Gene Colan, Steve Ditko, George Roussos, Dick Ayers, John Buscema, Paul Reinman, and others who would form the core of the 1960s Marvel Bullpen of artists were among the creators working on these books, then stuck around for the fun later.

Stan and company saw the success of National Periodical’s reboot of The Flash and Green Lantern, and then the rolling these two heroes plus Aquaman, Wonder Woman, and Martian Manhunter into the Justice League of America in early 1960, courtesy of Gardner Fox. Lee and Kirby’s first foray into superheroes would be the Fantastic Four in November 1961, followed by introductions of Ant-Man, the Hulk, Spider-Man, and Thor in 1962.

I’m not going to recap the Marvel Superhero play-by-play. Been done elsewhere, and likely done better than I could. What I do want to point out are Stan’s writing and editorial responsibilities under Marvel from 1961 through mid-1972 when he left the Editor-in-Chief job to become Marvel’s Publisher. He was not coasting, as some might think.

This image shows Stan’s responsibilities from this period. Click the image to scroll around–it’s a large image. The light blue areas are those titles that Stan was credited with writing. Stan may have had other people editing in the mid- to late-60s, but that is uncredited if he did. Therefore, Stan is assumed, by me at least, to be the sole SENIOR editor from 1961 through 1972 when he left that position.

Current counts on the above image for all years in January (except November 1961 / Fantastic Four #1) indicate that Stan was responsible for and credited with writing and editing the following number of titles PER MONTH at Marvel Comics (data from the Grand Comics Database):

Nov 1961 – 11 titles*

Jan 1962 – 12 titles*

Jan 1963 – 14 titles*

Jan 1964 – 17 titles*

Jan 1965 – 19 titles*

Jan 1966 – 14 titles + 3 editing

Jan 1967 – 9 titles + 9 editing

Jan 1968 – 7 titles + 11 editing

Jan 1969 – 6 titles + 14 editing

Jan 1970 – 5 titles + 15 editing

Jan 1971 – 4 titles + 14 editing

Jan 1972 – 2 titles + 9 editing

* Monster/SF stories in Tales of Suspense, Tales to Astonish, Strange Tales may also be done by Stan.

Yes, Stan had other writers for some of this period — and Roy Thomas was likely an uncredited assistant editor, but GCD data is designed to accurately reflect credits as listed in each of these books. GCD also reflects those other writers’ work as Stan steps away as writer through the 1960s. Some of the titles were staggered bi-monthly, so that provided some breathing space, but Stan held responsibility for the book month-to-month. Can credits be fudged? Sure. But, we will run with the info as given in the books and collected by GCD. Imagine that workload every month for twelve years. If this is accurate, then I am surprised Stan and the Marvel Bullpen survived it, even though there were 27 titles at Atlas/Timely before the 1957 distributor loss.

As I stated above, I believe the “Stan vs Jack” debate is based on a false dichotomy. Did Kirby and Ditko create plots and characters apart from Stan Lee input? Probably so. Was Stan only providing dialog for many titles, not full plot and scripts? Not a doubt in my mind. Did credit for some activities get mis-attributed over time and due to faulty recollections — and perhaps owner and executive-level shenanigans? Can’t believe that it didn’t.

But, nothing may have come of the Marvel Universe if this team had not come together. The creative engines of Kirby, Ditko, Heck, and other artists in the Marvel Bullpen generated the art, some of the plots, co-created characters, and crafted events, while Lee crafted the dialog and overall story continuity that held the whole together with common threads and events. Pull away one or two of this cadre, and Marvel might have gone the route of a failed experiment.

What this insane writing and editing method — often referred to as “The Marvel Method” — created was internal consistency and continuity over the whole of the superhero line through the 1961 to 1968 period.

As Chris mentions in his discussion on Continuity, the concept of continuity need not fetter creative writers or artists, any more than pointing out that Ben Grimm doesn’t wear a cape. There are rules and history to comic book characters in the 1960s Marvel Universe that give it something that Edmond Hamilton and Gardner Fox were slowly working toward with the Superman Family, Krypton History, the Legion of Superheroes, the Justice League of America, and the reboots of Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkman, and Atom — namely filling out a history for characters that had only been portrayed as having unconnected adventures and disconnected timelines from those events.

Specifically, 1960s Marvel provided verisimilitude and continuity to characters, allowing characters to experience consequences that mattered to the story, and thus to the readers. When Sue and Johnny’s father died in Fantastic Four Issue 32, it was a permanent change for them and the rest of the team. When the Thing crushed Doctor Doom’s hands in Issue 40, it was a driver for Doom’s revenge twenty issues later in Issue 60 — there was memory of the insult and damage, the thirst for Doom’s revenge upon the Thing, creating an element of verisimilitude for the readers. This is how readers expected the arrogant Victor von Doom would behave — it made sense and it felt “real” to them.

Chris’ page on “How to Make Great Comics” highlights this formula, but I believe that Chris, Stan Lee, and Jack Kirby were on the wrong track by calling it “Realism”. I believe the word they wanted was “Verisimilitude” — it needs to feel or appear real enough to generate belief. It does not necessarily need to be “real”, but rather “real enough”.

The scientific jargon Reed Richards uses doesn’t have to come from a real-world physics text, but it needs to be believable enough to the reader to give that impression to the story. The verisimilitude benefits from continuity and is reinforced by it. Discontinuity tends to pull the reader out of the story.

What is clear is that when Marvel was sold in 1968, the bonds of continuity and verisimilitude were being damaged and ultimately removed. With that removal, the quality of the books began to suffer. Under the sale, Marvel was no longer under the agreement with National Periodicals to limit the number of its titles, and that number almost doubled in two years.

But, the creative engines that built the 1967 Marvel were leaving or had left. Working within those externally imposed limits may have also contributed to the 1960s Marvel’s sharp writing, tight pacing, and innovative art. The quality of the books declined rapidly with the onset of the 1970s, and this was quickly seen in the sales.

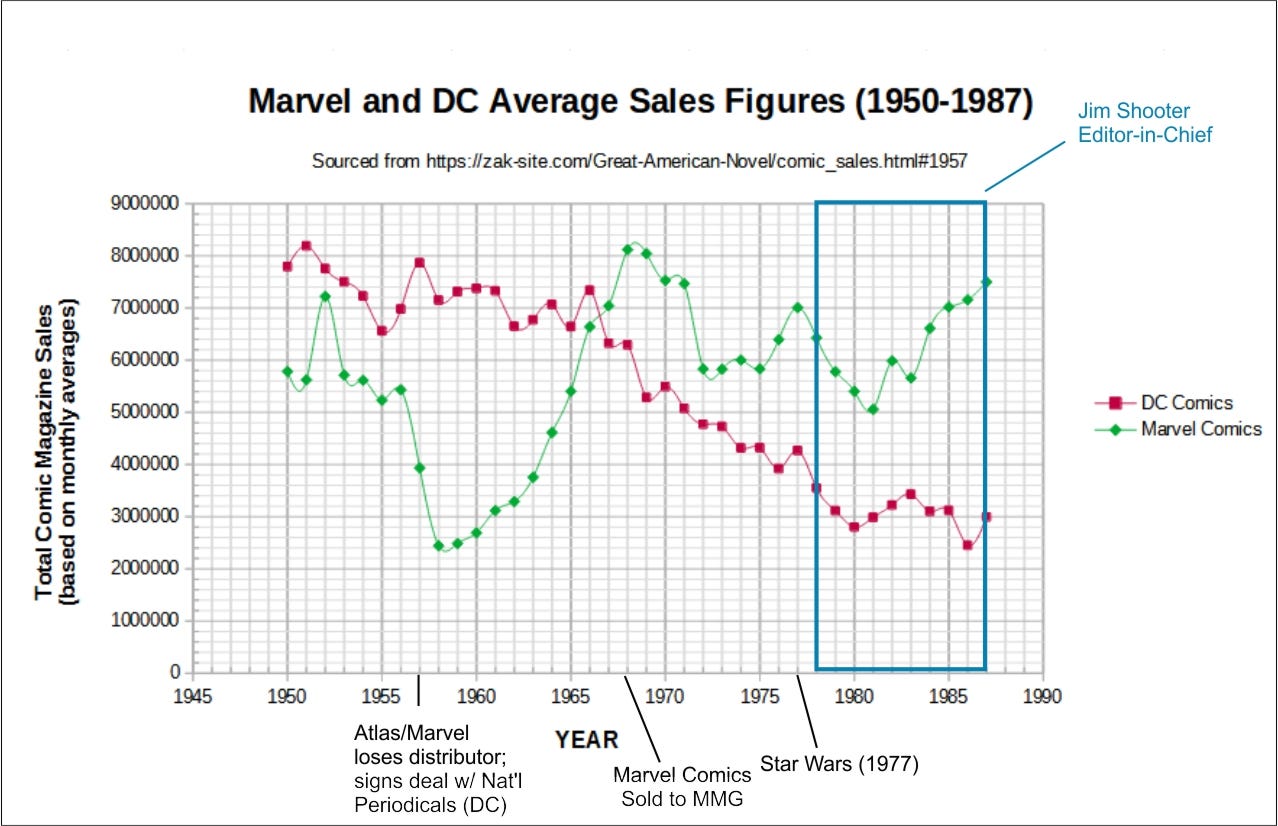

I re-created the graph that is on Chris’s page discussing the Marvel Universe and how it lost its way. My version removes some of the sharp peaks and adds a few real-world events against the sales curve. Note that the Marvel upward peak in 1977 is likely from Roy Thomas convincing Marvel senior leadership to allow him to create a 6-issue mini-series of the new movie Star Wars, which is credited with saving the company from bankruptcy.

That 1968 sale and the change in the fortunes of Marvel are well-aligned, though not causally linked via this data. So we have correlation vs causation event here — but correlation is strongly predictive. Stan brought over 35 years of experience managing creative teams and writing dialog for comics to the fore for Marvel’s success.

Notice how many people attempted to assume the Editor-in-Chief role after Stan left it, and were only in the job a year or two. It was not until Jim Shooter took the Editor-in-Chief position that Marvel’s sales fortunes began to turn around. Shooter demanded hewing to a universal continuity for Marvel. Though the creative talent chafed against it, sales improved throughout Shooter’s tenure, and declined after his departure.

It is worth observing that the two Editors-in-Chief who practiced or demanded continuity were the most successful in financial benefit to the company.

Chris has several pages on his site under the headings “Marvel Comics” and “What Went Wrong”. These are all worth your time to read if you are interested in how Marvel Comics lost its way, partially recovered under Jim Shooter, then resumed its downward decline with DC Comics after Marvel fired Shooter.

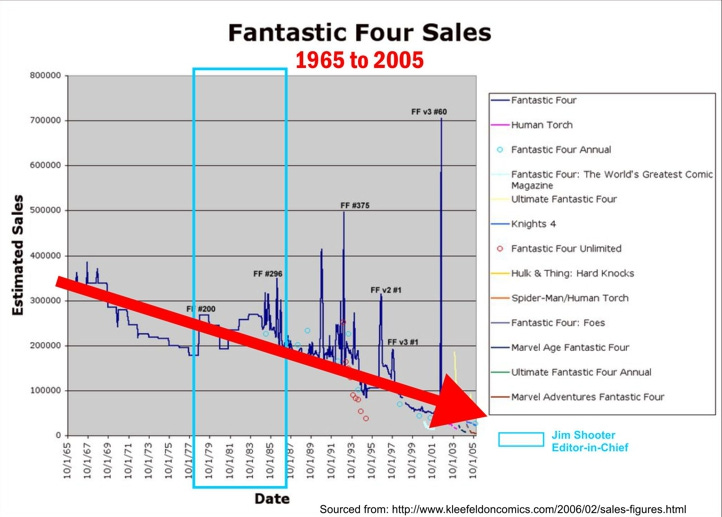

Sean Kleefeld discovers similar data in his research through 2005, and we again see the “Shooter Bump”. The general trend for comics sales continues to be “down”.

WHAT CONCLUSIONS CAN WE DRAW FROM THIS INFORMATION?

History should be a good teacher when it comes to running a business in a specific sector. Look for mistakes that others make, and learn from them, rather than making the mistake yourself. Based on the following examples, I’d guess that business leaders just don’t learn without a solid PowerPoint summary slide.

In the early 1940s, Lev Gleason Publications was waxing poetic on the competition with only four published comic books in their stable — Silver Streak Comics, Daredevil Comics, Crime Does Not Pay, and Boy Comics (starring Crimebuster), and featuring art by the stellar Charles Biro. In 1948-1949, the publisher was smelling money and chose to more than double their line in that period. The company talent couldn’t keep up with the pace and quality suffered. Gleason went out of business in 1956.

Over a three month period in 1975, DC Comics launched the “DC Explosion”, releasing 57 new titles into their stable. This was during the 1973-1976 comic book downturn. Economics forced DC to reverse their decision in 1978, resulting the “DC Implosion”, where the leadership chose to cancel 40% of their entire line. Cancellations were made before many story lines in the titles were concluded, further angering readers who had stuck with the company through this period.

A third example was Martin Goodman’s Seaboard Publications’ Atlas Comics. Formed by Goodman after his sale of Marvel Comics in 1968, Atlas Comics began releasing a flood of titles in mid-1974, including 5 magazine titles and 23 comic book titles. Even though some well-known and well-regarded creators worked on these books, creative teams were swapped out at the issue 2 or 3 mark, characters were redesigned and renamed mid-storyline, and no connectivity between titles existed. No book made it past issue 4, and the company shuttered in late-1975.

Post-1968 Marvel is a similar case of assuming your resources are expandable without sacrificing quality. Typical ‘suit’ move. And this would not be the last time this would be tried. Both Marvel and DC have difficulty with ‘lessons learned’.

A number of points for consideration are raised by Chris in his analyses of what made Marvel great and the cost of comics, and they deserve your attention and time to read.

These points stand out for me:

(1) Don’t make Stan’s cardinal mistake of Post-1968 Marvel — “Fans don’t want change; they want the illusion of change.” No. Your audience wants meaningful change, change that matters, and change that impacts the story. They want verisimilitude with their story, and continuity aids that verisimilitude. Don’t be afraid to set out some basic rails that bound your story, your characters, and your book. Continuity is appreciated by the audience. Continuity is not your enemy.

(2) Quality is vitally important with verisimilitude and continuity. Quantity may have a quality all it’s own, but in comics all that means is that you may be creating fireplace kindling rather than audience entertainment. That doesn’t mean that all your art must be at the level of Alex Toth, or that your script features award-winning prose every time. You cannot gloss over the need for bringing your best effort to your work. Producing more books or titles probably will not cover over your unwillingness to deliver quality. In fact, there is strong evidence that ignoring quality in favor of quantity may destroy you in short order with comic books.

(3) Listen for, ask for, and act on quality feedback. Your customers may not always be right, but you’d better understand what they are saying and why. Your artistic muse needs to be balanced with what the audience wants for its entertainment. None of this means compromising your morals or ethics. As modern comic stories have demonstrated — retrofitting popular characters, or killing off then resurrecting characters repeatedly, then putting those scenarios on reset-and-replay — will probably create some heartburn with a significant portion of your audience. And, you may never know it because the majority will likely just walk away and not come back to tell you.

That’s it for now. More on distribution next time.

Background Links.

Kleefeld on Comics – Sales Figures

Charles Biro

Progress and Process, Part 1

Progress and Process, Part 2

Comic Book Prices versus Minimum Wage

Grand Comics Database

The Cover Browser

The Comichron

Chris Tolworthy’s ‘The Great American Novel’

Fascinating read! I'm enjoying this trip through the past, seeing how things got to where they are now. As a kid I watched the TV shows of Batman, Spiderman, etc because the only comics I ever saw were too adult for my tastes.

Dynamite article. When I was a kid, I still got most of my comics through newsstand spinner racks, either at the local Rite-Aid, Dollar General, or the local newspaper distributor, well into '93. Only in about 1991 did we get our first local comic shops, and they started out centered on sports cards. I'm not sure whether they adopted comics first or started them because of the popularity of non-sports trading cards, many of which were comic related. Now the new card market is almost entirely dominated by Magic, Pokemon, Yu-Gi-Oh, and the like, a whale that has also eaten the game and hobby stores that used to sell a much wider variety of material like Role Playing Games not made by TSR/WOTC and miniature wargames not made by Games Workshop.