POSTS IN THE SERIES: Post 1 Post 2 Post 3 Post 4 Post 5 Post 6

Note 1: I am currently working on one or more posts discussing the American comics codes and their effects on publishing, as well as the furor(s) that surrounded them. Life has once again intruded these last few weeks, but with luck, sometime next week you should see the first one posted. In the meantime, I am reposting a series of six articles that I wrote about two and one-half years ago on American comic book history. I might make a few corrections along the way. We’ll see.

Note 2: I do not strive to be either academically rigorous nor authoritative in my analysis, and I’m an opinionated cuss. Other authors have spent a great deal of time interviewing the principle actors and performing rigorous historical research, therefore I lean heavily on those individuals who did the heavy lifting on this topic. My posts are meant to review some results of these researchers’ data and findings, as well as examining other artifacts of comic book history, to attempt to find general or overarching patterns that may inform and guide current and future creators of comics. References to the sources I use will be provided at the bottom of this and future blog posts.

Note 3: Some of these posts are gonna blow up your e-mail. Sorry ‘bout that.

To start this fifth post on comic book history and the search for “Marvel Magic”, we first return to Jim Shooter discussing his duties as Editor-in-Chief at Marvel Comics in 1978:

“The comics business went into a steep decline in the ’50s and early ’60s. During that time a lot of companies folded, a lot of comic book professionals were unemployed, and so, if you were an editor at a surviving comic book company you never had to train anybody, you knew lots of guys who were out of work. The streets were awash with unemployed cartoonists. So what happened is we had a generation gap—relatively few new people came into this business between the mid-’50s and the early-to-mid-’60s. Around that time a few of us started to trickle in. Among the arrivals in the early to mid-‘60’s were E. Nelson Bridwell, Roy Thomas, Archie Goodwin, Neal Adams, a few others and me. We were pretty much the last guys who got to learn our craft from the older guys–the guys who really invented and built the comic book business.

. . .

“There was a GENERATION GAP in the comic book industry. There were some people in their 50’s and 60’s, there were a lot of people in their twenties and early 30’s, but not enough in between. Because there had been an extended period of decline when relatively few new people came in, we were missing a generation.

“What that meant is that young guys who should have been assistant editors to a forty-something person were instead editors or editors in chief, even though their main qualification was having read 10,000 comics.”

Roll this bit of information back to 1968. The Marvel staff that remained through 1978 would have been in their 40s and 50s in 1968 by Shooter’s estimation. These folks would be Greatest Generation with some very early Silents. The generation gap that Shooter speaks of would be Silents who were generally unable to break into the industry in the late 50s and the 60s due to the downturn in the industry. Greatest Generation creators hung on to the majority of remaining positions. Those new staff at Marvel would have been in their late teens and early 20s in 1968. Those individuals would be Boomers.

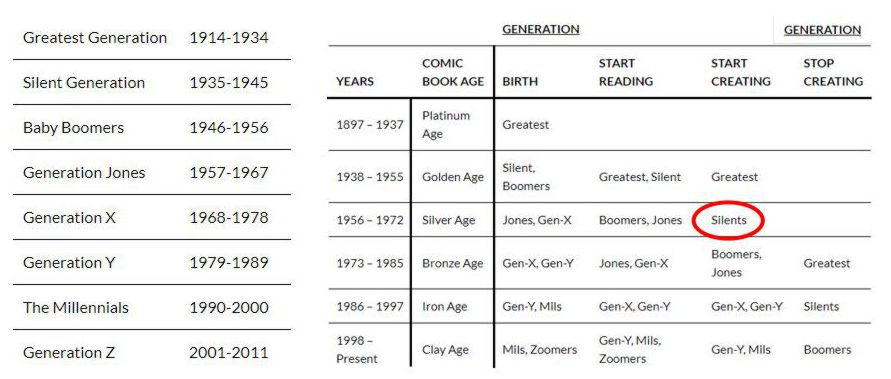

Recall the Comic Book Ages and how the Generations map to the Ages.

We see a significant cultural divide here in 1968 if what Shooter says is true.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO UNDERSTAND THIS CULTURAL DIVIDE WHEN IT COMES TO COMICS?

There is a hole in the “Start Creating” column for the Silver Age where the Silents should have been. The Silents didn’t show up for the Silver Age except for a few who managed to break into the field during the tight economic times. Comics creators between 1968 and 1978 were generally being split between Greats and Boomers.

Fewer Silents were available to convey the comic book culture from the Greatest Generation to the Boomers. The Greatest Generation fought WWII and the Korean War, Silents watched their elders fight these battles, while Boomers protested the Vietnam War. These generational divisions carried across other cultural divisions.

Boomers worked to upset the work done by previous generations — this is critical to understand in comics as it is in other media. We will see that this response by Boomers to works created by other generations began to reflect in comic books as Boomers were given authority earlier than they normally would if more Silents had been in the organizational structure.

1968: THE BREAKPOINT YEAR IN WESTERN CULTURE

What was going on in 1968? Besides the sale of Marvel Comics, here are a few other items. (More in the background links at the bottom.)

Soviets invade Czechoslovakia, USS Pueblo captured by North Korea, assassinations of RFK and MLK, Action for Children’s Television attacks Saturday Morning cartoons, Tet Offensive and My Lai massacre in Vietnam occurred, the 1968 “Hong Kong” Influenza Pandemic (H3N2 virus), college campus protests occurred in the US and other parts of the world, the Chicago Democratic Convention and associated riots, US and North Vietnam agree to Paris peace talks, Black Power movement protests at Summer Olympics, NOW protests the Miss America Pageant, Apollo 7 and Apollo 8 launched, Richard Nixon was elected as US President.

Why is this important? The change in outlook between Stan — a Greatest Gen who served in WWII — as Editor-in-Chief and subsequent Editors and Writers is evident after Stan stops writing and turns over all direct creative activities to others in 1972. Who were those other people who took the reins?

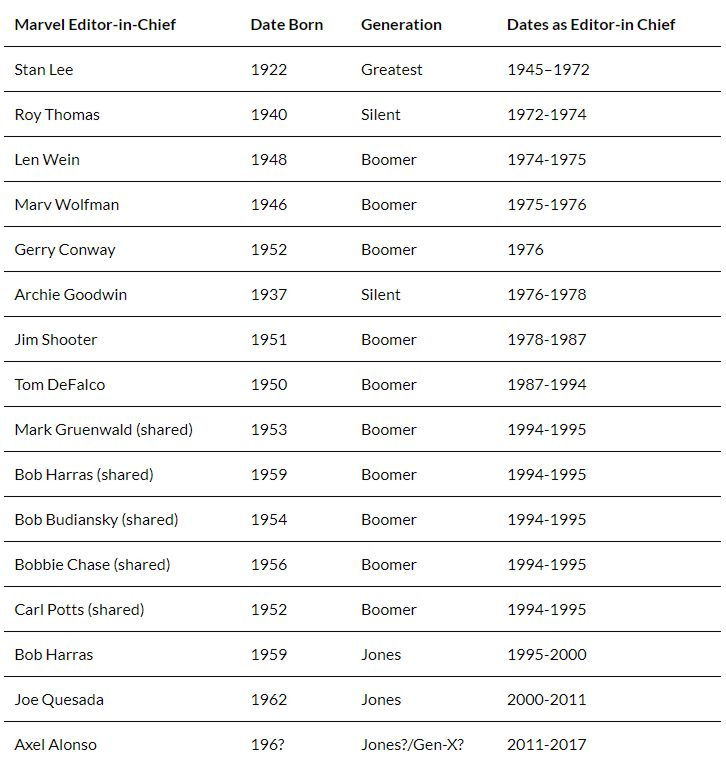

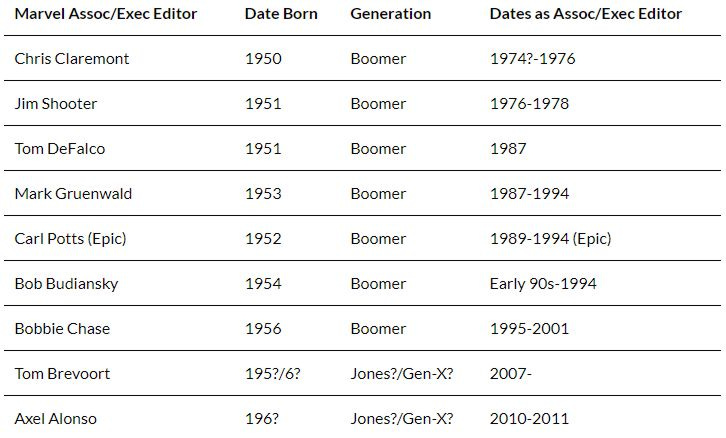

Let’s lay out the Editors-in-Chief as well as the Associate Editors/Executive Editors for Marvel Comics and look at their Generational position.

Shooter mentions two people he met and worked with at National Periodicals when he began work at the company, somewhere between 1965 and 1969.

E. Nelson Bridwell (b. 1931/Greatest Generation) was a National Periodicals/DC Comics writer, assistant editor, and editor under Mort Weisinger.

Neal Adams (b. 1941/Silent Generation) was a comic strip artist, comic book artist, and cover artist for National Periodicals/DC Comics.

Let’s shift focus to Marvel Comics from 1945 to 2017.

This pair of tables shows that the reins of Marvel Comics transitioned from Greatest Generation creators and editors, skipping a moderating influence by Silents, to an almost exclusive editorial rule by Boomers from 1972 to at least 1994. Generation Jones and Gen-X only began exerting an editorial influence at Marvel Comics as of about 1995. Boomers finally abandoned the reins of editorial leadership, essentially after the post-1997 cultural collapse.

GREATEST GENERATION AND BOOMER GENERATION: THE GREAT DIVIDE

Since the 1968 division at Marvel Comics was between Greatest and Boomers, rather than Silents and Boomers, what were the points of difference before and after Stan’s departure from an active writing and editorial roles in 1972?

Stan had decades of writing a wide range of genres for comic books, to include Westerns, Romance, Mystery/Horror, Humor, and Superheroes comics. A read through of Stan’s work from 1945 through 1972 showed that he was not averse to blending genres. Working with Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, Don Heck, and other Greatest Generation Marvel Bullpen artists, the 1957-1968 Marvel stories had a distinct Pulp feel, trending toward Futuristic Adventure fiction vice Mythic Adventure, even for books like Thor, but also shot through with elements of Classic Romance.

Marvel’s output from 1957-1962 was predominantly Romance, Western, and Monster/Mystery/Horror stories, gradually adding Superheroes between 1962 to 1963, and dialing down and retiring most of the other genres from 1965 to 1970.

The general Futuristic Pulp feel continued throughout most titles through the 1957 to 1968 period. As discussed in previous posts, departures of Steve Ditko in 1966 and Jack Kirby in 1970 removed two of the biggest creative engines from the Marvel Bullpen.

Jim Steranko and Neal Adams were the hot new artists of the late 60s, but the new leadership at Marvel blocked directions Steranko was taking, so he departed for other media. Other Bullpen artists were less enamored of the Superhero line and were more interested in the titles testing the Horror, War, Romance, Science Fiction, and other genres from 1969 to 1976.

The economic downturn from 1971 to 1976 also impacted comic sales across the board. This didn’t bode well for the Superhero lines that were the meat and potatoes of the company in the 60s. Departures of 1960s artists meant that new talent and other working artists were brought on to work at Marvel in this period prior to Shooter joining Marvel in 1976.

This is the mix of Greatest and Boomer creators that faced Shooter when he took over as Editor-in-Chief in 1978, and the reason for his creation of his mini boot camp courses for comic book creation. Even the 1978 book by Stan Lee and John Buscema, How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way, was clearly designed to fill in some of the gaps due to the lack of commercial art trained artists and those whose training was limited to learning primarily from reading comic books.

Shooter himself mentions that at least some of these new people didn’t have the comic book creation background that the older generation possessed. It was also clear from the change in direction and themes of the stories that the sensibilities of the Boomer Marvel Bullpen were not the same as those of the Greatest Generation Marvel Bullpen.

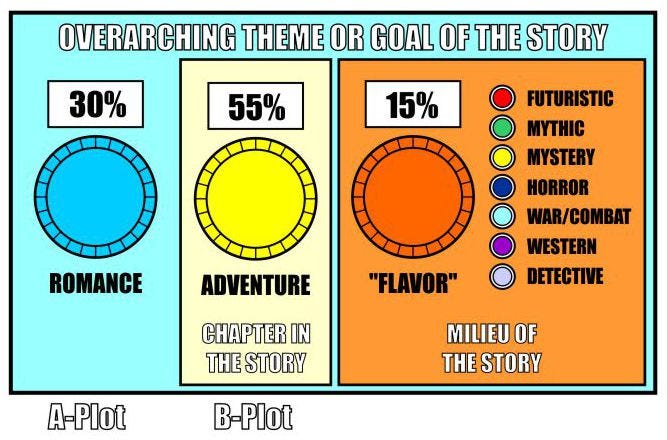

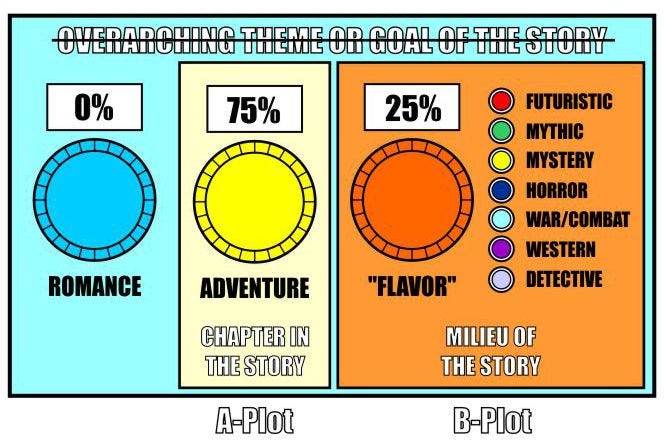

Stan, Jack, Steve, Don, and other creators from the Greatest Generation Bullpen had a creation process that looked more like the dials we introduced in the last post. The overarching theme for the series was as at least as important as the adventure within the specific issue.

The Boomer Bullpen and their “Me Generation” sensibilities over time generated stories that were more along the lines of this set of dials, typically eschewing the Greatest Generation sensibilities.

Let’s consider both the Fantastic Four pre- and post-Issue 125 and the Amazing Spider-Man pre- and post-Issue 110 which were Stan’s last projects as a regular front-line Marvel writer.

FANTASTIC FOUR PRE-ISSUE 125 & AMAZING SPIDER-MAN PRE-ISSUE 110

The FF is in general, focused on over-arching family based themes. A love triangle exists between Reed-Sue-Namor, until Reed and Sue are married in FF Annual 3. FF Annual 6 focuses on the birth of Reed and Sue’s son, Franklin. Issues 87-90 show the couple looking for a suburban home to raise their family.

Ben Grimm, Reed’s best friend and mentor, meets Alicia Masters and many issues feature the Thing’s challenge to form a relationship with her. Johnny Storm is Sue’s brother and Reed’s brother-in-law. He’s also Ben’s on-and-off tormentor and kind of his younger sibling. Johnny meets Crystal of the Inhumans and Johnny becomes her boyfriend through Stan’s run. Until Kirby leaves after Issue 102, this family focus is very intense, though it falls off a bit with Stan at the wheel from 103 to 125.

The family focus is the overarching Romance element from Issues 1-125 on the Superhero dials, with the Adventure and Flavor elements being the battles with antagonists and villains from issue to issue. Especially in the Stan-and-Jack era between FF Issues 1 and 102, and less so in the Issue 103 to 125, the Superhero dials are set to Romance taking the A-plot.

The A-plot is focused on the character relationships, their personal and overarching goals, and how they change their interpersonal relationships, to include the villains and antagonists. The B-plot is typically the Adventure and Flavor elements that surround the A-plot.

Amazing Spider-Man follows Peter’s challenges with balancing attending high school/college, providing for Aunt May’s health and welfare, earning money and dealing with J. Jonah Jameson, and forming relationships with various people in his life, to include Gwen Stacy, Captain Stacey, Aunt May, Harry Osborne, Mary Jane Watson, Flash Thompson, and others. Like the Fantastic Four, these elements form the A-plot of Spider-Man during the Lee-Ditko years and the majority of the Lee-Romita issues, with the B-plot again being the Adventure and Flavor elements of the story.

FANTASTIC FOUR POST-ISSUE 125 & AMAZING SPIDER-MAN POST-ISSUE 110

Reed and Sue consider divorce after they separate over an accident involving Franklin, not reconciling until Issue 150. Franklin himself is depreciated significantly from the stories, and doesn’t age at the same rate as the other characters, indicating that writers and editors lost the bead on the character for long periods of time.

Crystal develops allergies to “pollutants” and is forced to permanently (or as permanent as anything in modern comics) relocate to the Hidden Land, removing her from FF continuity, and leaving Johnny again as the perpetually-immature teen-age hothead. Ben and Alicia’s romance is kicked to the curb except for periodic returns to involve tedious break-ups and reconciliations. The overarching elements of A-plot that the Greatest Generation Bullpen created are depreciated over time in favor of hunting villains as the A-plot by the Boomer Bullpen.

There is little in the way of husband-and-wife interaction between Reed and Sue in this period, nor is there much in the way of family interaction at all. Ben and Johnny are teammates with focus on banter, and little as friends. The family is depreciated heavily from Issue 125 forward.

Here, the Romance dial is gradually turned down to zero, ramping up the Adventure and Flavor dials, focusing on the A-Plot of “Hero Punches Villain”. The B-Plot is typically relegated to the actions of the milieu characters and events in the background, which are almost exclusively dealing with Adventure elements for a future issue, i.e. “Hero Punches Villain, Part 2”.

Similar changes for Amazing Spider-Man were detailed in Part 3 of this series of posts. A move to the main character’s individualism, less focus on family and friends, less concern for overarching character goals, and how those goals were achieved, led to similar outcomes for Spider-Man.

A-plot became merely combat with featured villains and how that outcome affected Peter Parker, while the B-plot became the Flavor–environment and its trappings, to include the now almost irrelevant friends, family, and associates, since the story was now all about Peter.

BOOMERS WORK TO UNDO THE GREATEST GENERTATION’S EFFORTS

We see in these two titles the distinct generational split between the unified-vision, long-term editor in Stan Lee with Jack, Steve, Don, and the Greatest Generation Bullpen members, and the multiple-editor driven Roy Thomas/Archie Goodwin/etc and Boomer Bullpen model. The Greatest Generation creators took more from the traditional Western Historical canon — focusing on romantic pairings (Reed and Sue, Ben and Alicia, Johnny and Crystal, Peter and Gwen), family formation (marriage and children), forging strong male interpersonal relationships (Reed and Ben, Ben and Johnny, Peter and Robbie, Peter and Capt Stacy, Peter and Harry, Peter and Flash), and investigating the interpersonal relationships of these smaller elements with other family, friends, co-workers, as well as antagonists and villains.

The few Silents and majority of Boomers took the lead on aligning the content of the books with the popular zeitgeist of the current day, moving the books away from aspirational themes of their Greatest Generation predecessors toward ‘realism’. That meant divorce, no marriages, no children, and few relationships outside of the ‘hook-up culture’ varieties. Traditional values highlighted by Greatest Generation creators were ignored, avoided, and eventually derided. Post-1968 sales figures that were shown in previous posts demonstrate the fruits of those efforts by the Boomer Bullpen.

While Shooter’s efforts to train the new creators who had little background in storytelling other than reading comics and his demand for the return to strong continuity within and between titles were successful, a review of the timelines of other media and cultural changes indicate that Star Wars may have had a much stronger effect in turning around Marvel Comics’ fortunes. Star Wars signaled a demand by the public for something other than the dark and moody stories that had infested movies and other media between 1966 and 1976.

Shooter’s strong personality, plus the Star Wars license acquisition to produce the comics, were a powerful enough force to pull the company out of its nosedive in sales for his tenure at Editor-in-Chief. But, little of the aspirational themes of the Greatest Generation returned to the majority of comic books in this period, meaning that when Shooter was fired, the decline in comics continued. The Boomer model of the Superhero dials was the standard model for comic book creation for decades, and essentially has not changed to the present day.

The Boomer Bullpen Model. It’s “Hero Punches Villain, forever.” Enjoy.

Not all comic titles after 1974 followed the Boomer Bullpen model, but the majority certainly did, and still do today. It’s not long before any title that diverges from that model gets drawn back down the Boomer Bullpen path, being less and less informed by the Western Canon if they are of the Big Two Companies or those emulating them.

It’s therefore no surprise that many comic books today are nothing more than “Hero Punches Villain” and self-insert, Mary Sue-driven narcissistic storytelling. How do we break this downward spiral for comics, if it can be broken?

CAN WE RECOVER THE “MARVEL MAGIC”?

Comic book storytelling is broken in the modern age. It’s broken in the same way it is broken for literature. It requires a return to the Western Canon to inform the core of story creation.

Creators must read and understand the old books of the Canon and those that descended from the Canon to discover why and how they lift up the spirits and souls of their readers.

Creators must grasp the structure of Classical Romance stories from whence all story genres originate. They must embrace creating aspirational Classical Romance stories, and take that type of story back to comic books.

Creators must reject the Boomer Bullpen Model. That is the key to the lost “Marvel Magic”.

As Jeffro Johnson has said many times: Regress harder!

Background Links

Timeline of 1968

The 1968 “Hong Kong” Influenza Pandemic

The 1957 and 1968 Influenza Pandemics

Biography of E. Nelson Bridwell

Biography of Neal Adams

Wow, this was incredibly eye-opening. It explains my utter inability to get into modern comics, and just how ugly and overly busy they are. All of my complaints are Jim Shooter's complaints, too, and I feel vindicated. Now I won't feel guilty about packing in more romance and interpersonal drama in between the flashy fights in my own comic.

This was eye opening. As a kid, I hated "romance" in comics and thought there was way too much of it because, as for example in X-Men or mid-90s Spider-Man, the "romance" was trashy Soap Opera style infidelity, drunken hook-ups, implausible mystery offspring/relatives, etc... It took my brain a long time to adjust to the idea that literature Romance actually meant something much more than this, and it took me even longer -- until this morning, literally -- to accept that it was OK for an adventure comic to put the Romance front and center. I often felt guilty putting personal relationships as the focus point in my own stories. In fact, I've written a lot more of than than I've published, as a lot of the scenes met the cutting room floor rather than 'spoil' the whizbang focus on fights and powers and fiendish plots.