POSTS IN THE SERIES: Post 1 Post 2 Post 3 Post 4 Post 5 Post 6

Note 1: I am currently working on one or more posts discussing the American comics codes and their effects on publishing, as well as the furor(s) that surrounded them. Life has once again intruded these last few weeks, but with luck, sometime next week you should see the first one posted. In the meantime, I am reposting a series of six articles that I wrote about two and one-half years ago on American comic book history. I might make a few corrections along the way. We’ll see.

Note 2: I do not strive to be either academically rigorous nor authoritative in my analysis, and I’m an opinionated cuss. Other authors have spent a great deal of time interviewing the principle actors and performing rigorous historical research, therefore I lean heavily on those individuals who did the heavy lifting on this topic. My posts are meant to review some results of these researchers’ data and findings, as well as examining other artifacts of comic book history, to attempt to find general or overarching patterns that may inform and guide current and future creators of comics. References to the sources I use will be provided at the bottom of this and future blog posts.

Note 3: Some of these posts are gonna blow up your e-mail. Sorry ‘bout that.

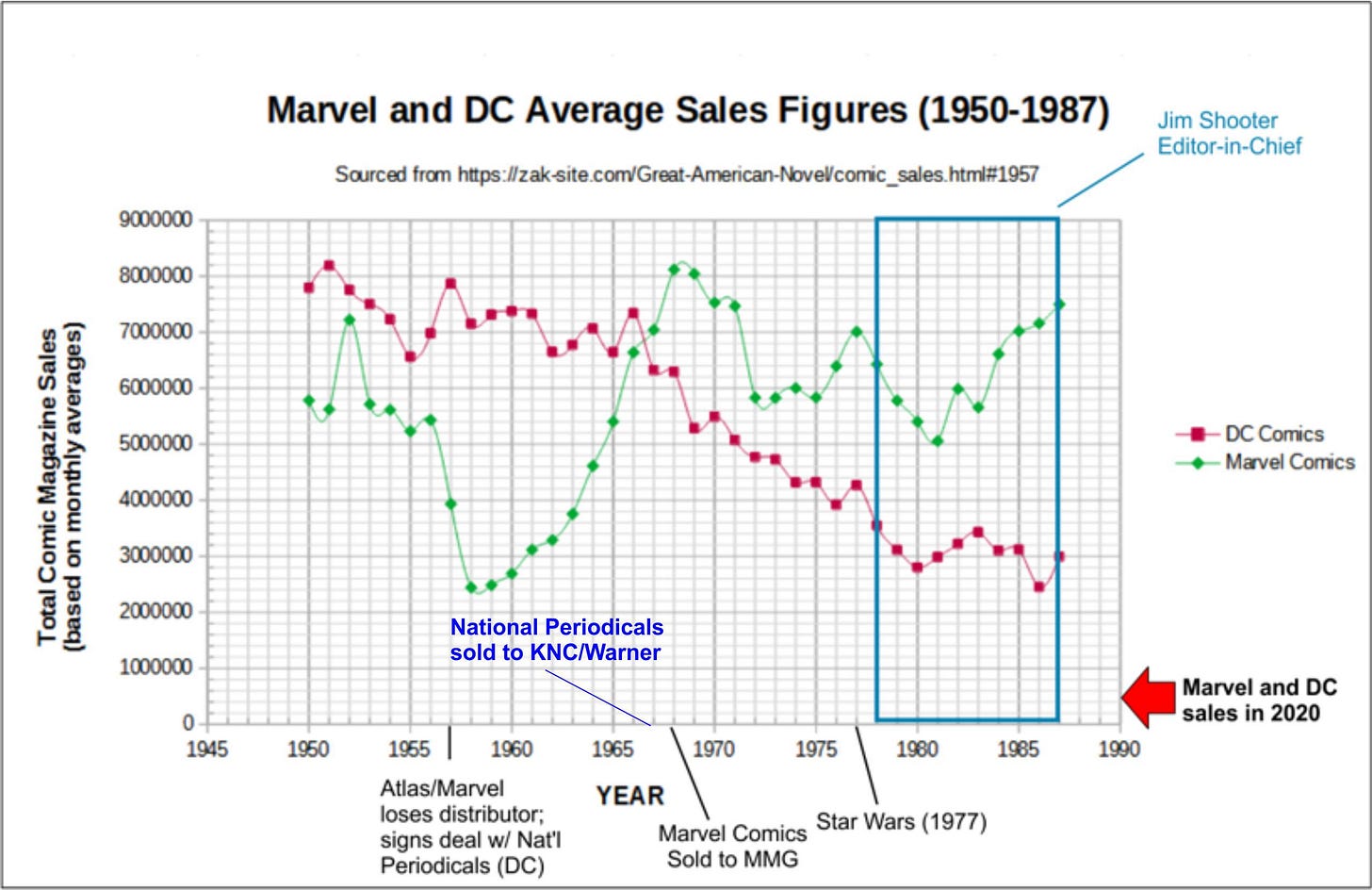

As discussed in the previous articles in this series, Marvel Comics’ deterioration began in 1968 after its sale to a corporate raider, and was exacerbated by the departure of Stan Lee from editorial and writing duties in 1972.

The premier of Star Wars in 1977 and Jim Shooter’s assumption of Editor-in-Chief duties in 1978 turned around the decline for a time, though sales once again began to drop after Shooter was fired in 1987. The change-over from the Greatest Generation old guard at Marvel to a significantly less learned and skilled Boomer Bullpen caused the departure from the Classical Romance themed stories that made Marvel Superheroes such a powerhouse from 1963 to 1968.

The poison of ‘realism’ — rather more ‘Materialism’ — that the new Bullpen and Boomer editorial staff brought to the titles began to take its toll on the stories and characterization, abandoning Marvel’s Classical Romance themes of the 60s, leaving little but traveling from one super-charged battle to the next, and ultimately devolving to base genre signaling.

But what about the Other Big Dog of Comics in 1968? What was National Periodical Publications doing at this time? First, let’s take a look at a little of the history of National Periodicals, known to us today as DC Comics.

National Periodical Publications was established originally as National Allied Publications in 1935, and grew from several comic book company acquisitions from the 40s through the 60s, eventually changing its name to DC Comics in 1977.

But that was after National Periodicals was sold.

As with Marvel Comics, a corporation bought up National Periodicals to add to its portfolio. Kinney National Services, Inc. purchased National in 1967 along with a number of other businesses, including Warner Brothers-Seven Arts. After further acquisitions and spin-offs, Kinney National Services became Warner Communications in 1972.

Two anchor points for National Periodicals were Mortimer “Mort” Weisinger and Julius “Julie” Schwartz. Both were also very active in Science Fiction fandom since the early 1930s. The pair formed the Solar Sales Agency literary agency to represent science fiction authors in 1934. Weisinger moved on to become the editor for Standard Magazine’s Thrilling Wonder Stories in 1936, then he moved to National Periodicals in 1941. Schwartz continued with the Agency until he was convinced to join All-American Comics in 1944 by one of the authors he represented, Alfred Bester, who was at that time writing for Green Lantern. Not surprisingly, National Periodicals had several well-known Pulp writers working for them to include Bester, Gardner Fox, and Edmond Hamilton.

See JD Cowan’s series on Science Fiction Fandom for more on Weisinger and Schwartz and their involvement in Science Fiction fandom activities.

BETTER:

has also collected this material with his other SF fandom investigations into a new book that you SHOULD read. → LINK

At National Periodicals, Weisinger edited Superman- and Batman-related titles early in his career, and was the long term editor for Superman titles until 1970. Schwartz took over editorial duties on Batman in 1964, shifting the character back to the Dark Detective format. But the top titles — Superman and Action Comics in the lead, with Batman titles following behind both — had been falling in sales since 1950 with the rest of National’s superhero titles.

There was a desire to try to re-invigorate sales, especially in comparison to the incredible sales performance of Marvel Comics between 1961 and 1968. Recall what the sales profiles of the top selling books at Marvel and DC looked like over this time.

National Periodicals began to lose its lead over Marvel Comics about 1966 to 1967. After the 1967 sale, National wanted to bring some new blood into the company to turn around the downward slide.

What changed?

Part of the answer is Charlton Comics.

In 1968, Charlton Comics editor, Dick Giordano, came to National Periodicals, along with writer, Denny O’Neil. Giordano was a long-term contributor to Charlton Comics as both an artist and eventually its Editor-in-Chief. In the mid-1960s, O’Neil worked for both Marvel Comics under Stan Lee and for Charlton Comics under Giordano.

These two were asked to revamp a number of National’s titles to spark greater sales, and hopefully capture some of the reader engagement that Marvel Comics enjoyed. These were not the only activities of this type, but they were some of the most obvious.

Dick Giordano worked on re-introducing horror, mystery/suspense, westerns, and other genres to test the waters just as Marvel did in 1969-1972. The art opportunities at National allowed him to work with Adams and other artists, but the editorial opportunities were lacking.

Giordano chose to depart National in 1971 with Neal Adams to form Continuity Associates. He would continue to freelance as an artist for both Marvel and DC through the 70s, and then return to DC in 1980 to eventually become DC’s Vice President/Executive Editor.

The difference at National for O’Neil as opposed to Charlton and Marvel would be working almost exclusively on Superhero titles. If there is one significant writer at whose feet we can lay much of the change from “Classical Romance” to “Realism” it is O’Neil.

Consider his significant assignment at Marvel Comics after Steve Ditko’s departure in 1966: writing for Doctor Strange. The dimension-spanning multi-issue battle against the tyrannical Dormammu had just concluded with Doctor Strange’s return to his home in Greenwich Village.

From the Grand Comics Database, this was Denny O’Neil’s idea for a 3-issue Doctor Strange story just after Ditko left the building following Strange Tales Issue 146. Partial plot synopsis of the Doctor Strange story from Issue 147:

Strange walks the streets of Greenwich Village and after stopping a robbery returns home to find his bills unpaid, his bank account empty, and a city building inspector informing him he has six months to bring his house up to code. He instructs Wong to sell some jewels to pay the bills, checks up on Baron Mordo, thinks back on recent events, and then contacts a theatrical agent, Hiram Barney, about a possible nightclub gig. But he’s told magic is “out”– rock bands are “in”!

[ Battle with Kaluu follows, with plotting help from artist Bill Everett ]

Gripping.

Upon returning to the title after O’Neil and Roy Thomas took their whacks at it, Stan cleaned up monetary concerns by having an exasperated Dr. Strange yell at Wong then conjure an enormous pile of money, jewels, and coins, after which Strange tells Wong to never bother him with these petty issues again.

This should have been a sea of red flags to Stan Lee and other editors about Denny O’Neil writing for Superheroes, as well as a red flag regarding Stan’s ability to write and plot for Dr. Strange without Steve Ditko.

This is what Denny O’Neil brought to National Periodicals. Let’s do a run down of his efforts at DC Comics begun in 1968.

Justice League of America Issue 66 was O’Neil’s first foray into ‘modernization’ of DC’s Superhero characters, taking over from Gardner Fox, one of the co-creators of the JLA with Mike Sekowsky. Martian Manhunter and Wonder Woman were quickly dropped as members, and familiar Superhero stories became full-steam ‘socially and politically relevant’ as of Issue 78.

[ Gardner Fox was “let go” from DC at this time. Be sure to read up on this gentleman to whom DC/National Periodicals owed a very great deal. ]

Wonder Woman Issue 178 (September/October 1968) ended an 80-issue run by Robert Kaninger and Ross Andru that updated the character and the supporting cast from the Golden Age to the Silver Age. Denny O’Neil began his run by removing Wonder Woman’s powers, vanishing Paradise Island, and changing Diana Prince a pantsuit-wearing, strong-woman adventurer in search of inner peace with the help of a blind wise man. The changes were deeply despised by Wonder Woman fans and by feminists who complained that one of the few super-powered heroines at the level of Superman was ruined. Kaninger’s return to the book in Issue 204 began the reversion to norm of the character, rapidly undoing O’Neil’s unpopular changes.

Green Lantern Issue 76 (April 1970) began the Denny O’Neil take-over of the flagging title. The book was changed to Green Lantern/Green Arrow. Plot lines featured ‘realistic’ events vice the typical interplanetary adventures. In fact, O’Neil pretty much confined GL to Earth to deal with ‘relatable problems’. Plots included the famous copycat drug stories (“Jeepers, Speedy is a heroin addict!”) in Issues 85-86 (Oct-Nov 1971), just a few months after the FDA-requested Amazing Spider-Man Issues 96-98 (May-July 1971) from Marvel Comics — with no Comics Code Authority stamp. These activist-driven issues drew positive recognition from the national media talking about how comics were ‘growing up’, but the media hype around the stories didn’t translate to sales. Issue 89, the environmental awareness issue, with its cover featuring an activist crucified on a jet plane engine, was the last issue of Green Lantern for four years.

Prompted by now-Superman editor Julie Schwartz, in Superman Issue 233 (Jan 1971) Denny O’Neil took over scripting, running through Issue 242. A research laboratory accident causes Superman’s powers to be significantly reduced, apparently to make him more relatable and vulnerable to readers. Simultaneously, the same event destroys all kryptonite on Earth by changing it to iron. Once O’Neil leaves the title, Superman’s powers are slowly returned and more kryptonite falls on Earth, rendering the series’ changes moot.

O’Neil’s work on the Batman titles conformed more to the original character, taking him back to his grim crusader against crime roots. Both Adams and Giordano assisted on many of the classic stories, such as the introduction of Ra’s al Ghul. O’Neil brought back classic Batman villains, to include Joker and Two-Face, and also returned them to their classic criminal personalities. These stories, along with the Frank Robbins era of Batman titles, set the tone that Frank Miller would adopt for his Dark Knight series.

Reviewing O’Neil’s output for National in this period, it’s clear that he never broke out of the very limitation he demonstrated during his very brief run on Strange Tales: He needed to bring the hero ‘down to earth’, to make him ‘relatable with modern problems’, and to make him ‘less superior than he is now’.

O’Neil’s comfort zone was perhaps street level heroes, such as Batman. He definitely wanted to deal with social issues rather than romance and adventure. The problem was that other than Batman, the characters he was given to write were mythic in stature and ability, and his response to them was to cut them down to his size. Clearly a failure on Schwartz’ part as Editor-in-Chief on these books in not recognizing O’Neil’s limitations.

Rather than writing the characters as they stood, O’Neil tried to whittle down the futuristic and mythic adventure heroes to be ‘realistic’ relative to his world. His 70s superhero stories don’t often stay fresh in the can for that reason. Sales results showed that while the stories could gain recognition and awards, they could not move books. Comic book readers didn’t want these kinds of stories.

This finagling was not limited to O’Neil. Robert Kaninger was also responsible for ‘modernizing’ storylines and characters to no effective value for average sales.

With Metal Men Issue 33 (Aug-Sep 1968), Kaninger returned to the title he created with the ‘hunted Metal Men’ series through Issue 36, then the Denny O’Neil/Len Wein team wrote Issue 37, introducing “new” Metal Men. The robots were given human appearances as a disguise to live in society as they hunted for the kidnapped Doc Magnus, with the expected sociopolitical accouterments. Mike Sekowsky wrote and drew the remaining Issues 38 through 41, after which the series was cancelled.

In Lois Lane Issue 93 (July 1969) with the first Robert Kaninger script, a de-powered Wonder Woman appears to compete with Lois for Superman. Kaninger shifted many subsequent stories to sociopolitical themes similar to O’Neil’s work, likely at editorial direction. Notable examples are Issue 106 when Lois uses advanced tech to temporarily alter her appearance to that of a black woman, and Issue 110 where she has custody of a Native American baby. These stories were rather out of place for the typical Lois Lane “try to marry Superman” story, but they did feature the new strong, independent Lois, who didn’t need no Superman —as much. Sort of. Maybe.

Amid this ‘realism explosion’, the comic book master of the fantastic, Jack Kirby, brought his very first “4th World” series to National Periodicals in Jimmy Olsen Issue 133 (October 1970). story. These stories ran through Issue 148 (April 1972). Three new titles were also part of 4th World: The New Gods Issue 1 (Feb-Mar 1971) through Issue 11 (Nov 1972), Forever People Issue 1 (Feb-Mar 1971) through Issue 11 (Nov 1972), and Mister Miracle Issue 1 (Apr 1971) through Issue 18 (Mar 1974). These titles stood in sharp contrast to the ‘Down-to-Earth Realism’ of many other National titles. DC also angered Kirby by having Murphy Anderson re-draw most of the faces on his Superman pencils without his knowledge.

Does this mean that these individual stories were necessarily bad? No, but it did mean that the writer was not writing to the character and genre as presented, i.e. the Superhero trope and its Classic Romance genre. The story itself might be worthy outside that theme, and in many case likely would have been better served in that case.

I argue most of the Green Lantern/Green Arrow stories fit into this category. While I was not a fan of O’Neil’s work in this title, I could see where these stories could be taken into a police procedural or street level adventure and do well. Breaking the Superhero isn’t an effective means of getting around a writer’s discomfort with the Superhero.

Taking into account a quote from Mort Weisinger as related by his assistant editor, E. Nelson Bridwell, there was a reason for Mort being the hard-driving boss:

“You’ve got to keep in mind that while there are a lot of people who’ve read about the characters before, there are always new people coming along, and you’ve got to realize that you can’t count on them to know the whole legend of the character.”

Did the post-1967 additions to National’s staff not know this? While I don’t know for sure, the evidence leans toward this answer being “NO”.

The end result of the ‘modernization’ of National Periodicals was no increase in average sales, which continued to trend downward until 1977-1978, with the Star Wars and Superman movies coinciding with a small bump in overall sales. The moodier, grim stories of 1969 through 1976 were no more wanted by National readers on the whole than they were at Marvel in the same period.

The end result at National was the same as it was at Marvel: DC’s Silents and Boomers shifted the themes of comics and comic characters from “Classical Romance”. They replaced Romance as the primary driver with Basic Adventure which was disconnected from any higher purpose. The same results as Marvel experienced took longer at DC, and didn’t have the benefit of a brief ‘Shooter Turnaround’. In fact, the “DC Explosion” of 1975 to 1978 likely did more to dampen the small 1977/78 sales spike than to aid it.

But the seed of Realism and Materialism was planted at both Marvel Comics and National Periodicals.

Were both driven by new owners looking to break sales slumps? Was this just a few people who didn’t understand the Superhero trope’s dependence upon Classical Romance for its appeal? Was it a dash to find new genres and modalities for comic books in an economic downturn during the early 70s? Was it some or all of the above?

Without some of the people who might know these intimate details, it is hard to say for certain, but what can be noted are the results.

New writers and artists at National Publications/DC Comics learned the same false lessons as those new staff at 1969 Marvel:

‘Realism’ gets awards and press coverage, but doesn’t help sales.

Readers don’t know what they want, other than new, novel, and modernized. “Illusion of Change” rules the day.

Classic Romance was out at both of the Big Two, which colored the landscape for all other remaining comic book companies, as well as any that might follow.

Why is all of this at all important?

It is necessary to recognize that the deterioration of comic books was a long, slow process. We think at times that the 1997/1998 break was something sudden and unexpected.

No.

Much as with many cultural erosion sites, the damage is done in small steps, increasing in a geometric fashion, so that when you begin to notice the effects, turning around the destruction may not be possible.

If comic books have a cultural value, then they need to be rebuilt from their very foundations.

To understand what the actual foundations *ARE* is our most important goal, so that the new edifice is not built on the sand of the old. In my view, Classical Romance and the genres which fall from it must be rediscovered and absorbed by new creators to effectively rebuild a culturally robust comic book ecosystem in the US.

Let’s get to it.

From what I know, you're spot-on about the Marvel bullpen and their retreat from classical romance influences. But I still see DC as more plot-oriented than character-oriented through to the end of the Silver Age and into the Bronze age. But then I haven't read as many Flash and Superman stories from the Batmania years and therefore have a skewed perception. Was DC stressing continuity and making character relationships like Clark-Lois and Barry-Iris consume the A-plot up until '68?

As soon as you said "they were active in the scifi fandom" I remembered JD Cowan's Last Fanatics series and went "uh oh". And they proceeded to do to comics what they did to the pulps, didn't they? Turned it all the gray goo. No wonder DC always lagges behind Marvel overall.